Debunking the ‘Del-Boy Fallacy’ and the universal myth of the entrepreneurial criminal.

OXA Insight from Dr Robert Smith, Visiting Professor of Policing and Criminal Enterprise, The Institute of Policing, The University of Staffordshire

Although the twin thesis of the entrepreneurial criminal and the entrepreneurial nature of Organised Crime are now accepted in policing and academic circles this briefing warns against accepting this as a universal truth. This is important because although there are acknowledged examples of both thesis in the literature and in practice the ‘Del-Boy Fallacy’ is often used to excuse non action by policing hierarchies who do not understand how to tackle such criminals. Moreover, using the label of criminal entrepreneur serves to reify and mythicise organised criminals who are not entrepreneurial per se. Not all criminals are entrepreneurial but there are key pointers available to identify if an organised criminal is entrepreneurial. This can be of great assistance to the authorities in correctly labelling an Organized Criminal [OCs] or Organized Crime Group (OCG) as being entrepreneurial.

There is an expanding literature in relation to the thesis of the Entrepreneurial Criminal. At a theoretical level the term has become accepted albeit it is a misnomer because it encompasses a wide variety of criminal typologies including - Entrepreneurial Criminal; Businessmen Gangsters; Dodgy Businessmen; Mafioso-Entrepreneurs; and Enterprise Orientated Criminals. Each typology has unique profiles and modus operandi. Even Craft Criminals and Villains have entrepreneurial traits to varying degrees. This conceptual blurring is important because there is no homogenous entity and no single approach to interdicting them. In addition, OCGs can be composed of a mixture of Crimino-Entrepreneurial types presenting as legitimate businessmen.

Another problem in utilising the term in a practical policing context is the acknowledged imbalance between the entrepreneurial capabilities of OCs and the Police. Most leaders and Senior Investigating Officers do not know how to deal with such entrepreneurial crime and criminals, nor how to bridge the resultant organizational gap. Thus, the police continue to employ the same old tried and trusted policing strategies and tactics. They simply do not understand its nuances. Decreasing policing budgets exacerbate the issue. Nevertheless, the result is that the often simply ignore the entrepreneurial nature of OCs and OCGs. This is where the ‘Del-Boy Fallacy’ comes into play as alternative voices warn of the non-entrepreneurial and anti-entrepreneurial nature of SOC whereby all OC is viewed as entrepreneurial when it is clearly not. This is quite a fitting descriptor because there is a tendency to reify and eulogise OCs as entrepreneurs when not all are entrepreneurial nor deserving of the social accolade of entrepreneur.[i] The label acts as a visual metaphor also acts as a meme. See the image below:

[i] The term was coined by entrepreneurship scholar Dr Lee Wainwright during a personal communication with the author in early 2024. For readers not familiar with UK popular culture Derek ‘Del Boy’ Trotter is a fictional entrepreneurial ‘wide-boy’ from the iconic television comedy ‘Only Fools and Horses’ which has become a particularly British social institution. The irony is that although Del-Boy has bought into enterprise culture he is not an entrepreneur per-se, but a wannabe embedded in the market trader fraternity and barrow boy cultures. He is a bumbling, hopeless trader. He operates on the margins of legality and criminality.

Figure 1 Derek "Del-Boy" Trotter

Source: Google Images

Establishing entrepreneurial provenance in criminals: To establish whether a criminal is entrepreneurial or not it one must profile them to determine key entrepreneurial markers. One must consider three elements – namely 1) Organized Crime Businesses [OCBs]; 2) the role of Playbooks in understanding routine behaviours / activities; and 3) the role of Business Models to analyse OC behaviours.

The term Organised Crime Business relates to an understanding that many OCGs operate more like legitimate businesses than organized crime groups and that utilising business theories and models could help in the war against organised crime.[i] Jailing OC foot-soldiers is not a sustainable way of interdicting OC because for every gangster or criminal jailed there were instant replacements. OCB thesis utilises the knowledge of how businesses operate to disrupt and deter OC activities and hurt them financially. OCB thesis compliments OCG thesis and is not intended to replace it. Moreover, is twofold because it identifies that some OCGs operate as businesses BUT it can also be utilised to analyse traditional OCGs by considering operational processes as business processes as complimentary elements to existing ones.

A playbook is a stock of set tactics or methods adopted by an individual or organisation in response to common actions.[ii] It can be a written formalised document, or an experience based informal knowledge base passed on in organisational stories and narratives. It can contain scripts, diagrams, or pre-ordained tactics and responses such as denials, obfuscations or orders. Criminal enterprises have the advantage of being able to accommodate illegal actions in their playbook responses than policing agencies in their playbooks if they have one. Police may not take much cognisance of it. The use of playbooks in organised criminal settings has yet to be properly researched although their use in terrorist settings has been documented.

A Business Model can be a written plan for the successful operation of a business, usually identifying sources of revenue, the intended customer base, products, and details of financing.[iii] In criminal circles it is an unwritten coda known only to the leadership of the enterprise. Policing agencies may not take cognisance of it. These three concepts add a new dimension on how to analyse and interdict OC actions and activities.

Organised criminal activities can be profiled to establish their entrepreneurial nature so that policing practitioners can correctly label them as entrepreneurial or not. Five key Profiling facets are discussed – 1) Criminal Facets; 2) Business Elements; 3) Semiotic Elements; 4) Narrative elements; and 5) Innovative Elements. See below[iv]:

1. PROFILING – CRIMINAL FACETS.

(Individual nominals and Collectives).

OCG – Organised along traditional criminal hierarchal structures with stereotypical criminal roles from boss, underboss to foot soldiers who self-identify as criminals ideologically and semiotically. They may may or may not adopt a criminal identity and may present as a Businessman Gangster or Legitimate Businessman and may operate legitimate and illegal income streams simultaneously. OCGs have identifiable Modus Operandi’s and Modus Vivendi’s. Most OCG members will have criminal convictions and be known to the police.

OCB – Organised along non-traditional criminal lines as a business with a CEO and business functions and may take on the appearance of a legitimate company. The OCB may be run by staff unaware they are a front for organized crime. Staff may self-identify with business roles, ideology and semiotics. The structure is fluid and may include legitimate and illegal shadow infrastructures. There will be an identifiable manager even if they are a figurehead only. Most OCB members will have no criminal convictions and be unknown to police.

Irrespective of whether one is dealing with an OCG or OCB one must profile what type criminal enterprise one is dealing with e.g., are they craft criminals engaged in one type of crime such as Theft, Robbery, People Smuggling, People Trafficking, Drug Trafficking, Gun Running, Fraud, Forgery, Smuggling Contraband etc. Although they may share similar structures and criminal strategies, they will have different Criminal Profiles, Skill Sets and Playbooks. The latter element is important because just like conventional MOs each OCG possess identifiable actions and responses it undertakes in committing its crimes but some of these will be unique to OCG acting as a signature. It is also helpful to map Law Enforcement playbooks to compare them with the those of criminal enterprises to identify organisational, communicational and skills-based mismatches.

2. PROFILING - BUSINESS ELEMENTS.

In engaging with OCGS the police approach their investigations based upon a foundation of tried and tested policing strategies, resources and tactics and seldom do they consider the Business Model of the OCG / criminal enterprise. Even if an OCG is profiled as a traditional one it will have a hidden business model underpinning its activities both illegal and legal. Developing an understanding of the business model of OCGs / OCBs is an essential element in understanding the operational nuances of its supply chains, its financial records, its structure, its logistical elements, and its communicational capabilities. OCG investigations rely more on traditional policing skills whereas OCBs require business related knowledge and skill including business analysts, not crime analysts, and business specialists, not investigators. OCBs are more difficult to investigate because they occur at a higher level than ordinary OCG activities because they take place in private business spaces unlike OCG activities which occur in street nd public places. It is harder to obtain intelligence about OCBs than in OCG settings because the police seldom have informants or knowledge of their business activities whether legal or illegal.

3. PROFILING - SEMIOTIC ELEMENTS.

The semiotic and aesthetic elements of criminal and entrepreneurial identities are very relevant and signs, and signals are always present if you know how to read them. There are many tell-tale semiotic clues which can be read by officers. For example, not many legitimate entrepreneurs require the protection of a ‘Minder’ or have an entourage of personal security whereas a gangster often travel in an entourage with a recognisable hierarchy of power. Many Corporate businessmen have a minder / bodyguard and a security detail, but the average businessperson does not require one. The aura of power and patronage and deprecating behaviour which emanates from the boss / foot-soldier relationship is palpable and readable. There are artefactual elements to both criminal and entrepreneurial identity and the criminal entrepreneur posing as a businessman will retain personal artefacts such as the ubiquitous bling which will betray their roots even when suited and booted. There are many other tell-tale signs which have their own symbolisms and rituals which play a crucial role in the constitution of criminal organizations and crimino-entrepreneurial identity.

4. PROFILING - NARRATIVE ELEMENTS.

Never assume that an OC is entrepreneurial. Profile everyone involved to determine if they are entrepreneurial or possess entrepreneurial traits and proclivities. Entrepreneurial criminals will have a proven history of possessing a dual entrepreneurial and criminal nous. The concept of nous is a mixture of intuitive and craft or skills-based knowledge learned on the job – thus a businessperson develops business nouse and a criminal – criminal nous. Neither can be faked or fabricated. Nous includes a knowledge of sharp practices, cunningness ad ruthlessness. Moreover, many have a family history of involvement in the small business community or having made their money as a self-made man. They will have either a business or criminal provenance backed up by a verifiable biography and a stock of personal myth and legends. Some of these will be apocryphal stories which circulate in the criminal or business fraternities. These will be broadcast by themselves primarily but may circulate in the community and particularly in the criminal fraternity. Some OCs may also have published or autobiographies. The best way to test for these is to speak to beat officers in the areas where the OC operates and even retired officers with an encyclopaedic knowledge of local villains. If there are no stories relating to criminal ruthlessness or business success or dexterity, then it is unlikely that a nominal is an entrepreneur.

5. PROFILING - INNOVATIVE BEHAVIOUR.

One of the major traits which identifies legitimate and criminal entrepreneurs from their peer groups is the trait of ‘Innovation’. The ability to innovate new solutions to ongoing business issues and problems is a driver of entrepreneurial and financial growth. In a criminal context staying ahead of the game by forensic awareness, new technology, new communicational strategies and devices is paramount to success. Thus, the criminal use of radio scanners, CB radios and the ability to neutralise alarm systems and defeat safes etc was the hallmark of criminal innovation. Nowadays, the ability to use new computer, new communications and the internet has revolutionised organized criminality to such an extent that the police are always playing catch up. The Enchrochat phenomenon is a recent example of criminal innovation. Therefore, it is essential that officers consider the innovativeness of OC players they encounter and make a note of any new communicational devices and in particular APPs which they use and pass these on to their techies for investigation.

Drawing tentative conclusions:

To recap, never assume that an OC is entrepreneurial. Profile each individually to determine if they are entrepreneurial or not. Entrepreneurial criminals will have a provenance of possessing dual entrepreneurial and criminal nous. They will have either a business or criminal history backed up by a verifiable biography and a stock of personal myth and legends / apocryphal stories. These will be broadcast by themselves and circulate in the community and in the criminal fraternity. Some may have published autobiographies. There will be telltale semiotic clues which can be read. For example, not many legitimate entrepreneurs require to be protected by a ‘Minder’ or an entourage of personal security whereas gangsters travel in an entourage with a recognisable hierarchy of power. The criminal entrepreneur posing as a businessman will often retain personal artefacts / ubiquitous bling betraying their roots. Entrepreneurial criminals display signs of being technologically and communicationally savvy and there will be evidence of innovation.

[i] The term was coined by policing scholar Professor John Coxhead.

[ii] Playbook Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster

[iii] See the Business Model Canvass of Osterwalder and Pinguer (2010) for a pictorial representation of the business model in action as an analytic tool.

[iv] Please note that the nine elements chosen by Osterwalder and Pingeur are their chosen elements and other business-related elements such as supplychain, or logistical issues could be substituted for one of the other elements. In a policing context it is helpful to complete a canvas for the policing organisation to compare against the targeted criminal enterprise to identify skills and resource gaps.

Violence Reduction at a Crossroads

OXA Insight from Professor Niven Rennie, Visiting Professor of Policy at the University of East London and Oxon Advisory Associate

In a new Report from Prof. Rennie the issue of violence, particularly among young people, is examined. It is a complex and layered problem that societies have grappled with for many years. Traditional approaches, often focused on enforcement and the heavy hand of the criminal justice system, have yielded limited success in achieving sustained reductions in violence.

A Public Health Approach

In 2005, the World Health Organization advocated for a public health approach to violence prevention. The Scottish Violence Reduction Unit (SVRU) was the first to adopt this approach, leading to significant and sustained reductions in violence in Scotland, particularly in Glasgow. This success has spurred interest and adoption of the public health approach in other regions, including England and Wales.

Learn More about our OXA Associates here

Violence Reduction Units in England and Wales

Following the establishment of the SVRU, several Violence Reduction Units (VRUs) were established in England and Wales. These VRUs aimed to adopt a public health approach to violence prevention, but with some differences from the Scottish model. Notably, the VRUs in England and Wales were accompanied by a statutory "serious violence duty," requiring agencies to share information and collaborate on interventions.

Challenges and Opportunities

Despite the progress made in adopting a public health approach, challenges remain. Data sharing among agencies, while improving, still faces inconsistencies. The link to Police and Crime Commissioners has also raised concerns about politicisation. Additionally, there is a fear that focusing solely on violence may not address the root causes of the problem, such as poverty and inequality.

Recommendations

To achieve sustained reductions in violence, a more holistic and community-based approach is necessary. This includes:

- Co-production: Working closely with communities to design and deliver services tailored to their specific needs.

- Addressing Trauma: Recognising the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and community trauma, and implementing trauma-informed practices.

- Social Impact Bonds (SIBs): Increasing the use of SIBs to fund preventative programs and achieve long-term demand reduction.

- Government Support: Ensuring government support and a clear focus on addressing the root causes of violence, such as poverty and inequality.

By adopting a comprehensive public health approach, working closely with communities, and addressing the underlying social issues, we can move towards a future where violence is significantly reduced, and communities can thrive.

Are you interested in learning more about violence reduction strategies and the public health approach?

Download the full report, "Violence Reduction Units at a Crossroads," to gain a comprehensive understanding of the complexities of violence and explore innovative solutions for creating safer communities.

Prevention: less crime, less costs, more public confidence

What prevention really means

Oxon Advisory Associate and EMPAC Professor John Coxhead

presented at the national Public Policy Exchange Conference on the 15th October 2024 reporting on the key research that shows prevention works better than reaction.

Given budgetary pressures on all public services, including policing, different ways of doing things is now an imperative. Although there has been value input from the Police Foundation (Muir, 2024) much of the current context concerns the volume, and costs, of demand, and consequently is as much about what the police should do, as about what the police simply cannot do.

There has been extensive policing adoption of research (Weisburd, 2012) concerning reactive tactics (such as hotspotting), which can aid some temporary alleviation of a problem already in its crisis state (a ‘hotspot’). Problem solving (for example, as developed by Eck and Spelman [1987] using the SARA model) is also essentially reactive because it is a response to an existing problem, to seek to reduce its reoccurrence.

These things, of course, all make sense – but only to an extent – as these represent Tier 2 (responsive) prevention. There will always be the need for a fall back situation where agile problem solving capability will be required, but the greater ambition and more affordable pragmatism would be to invest in Tier 1 (proactive) prevention, meaning to actually prevent, thereby removing the need to react.

Tiered policing

Response is tiered from immediate to delayed and scheduled, but is very expensive because of its resourcing requirements, and the demand upon it. This means the tiering of response has become triaged not only for capability considerations but also capacity. There is not enough reactive police capacity to respond to all the needs placed upon it. That is a fact within existing budgetary allocations, and these are likely to slip, meaning response as a sole model is unsustainable and at some point, unless other approaches are adopted, will simply collapse.

A collapsing reactive capacity will further dent public confidence, which is already at an all time low, and could well lead to private civil prosecutions against the police for a failure to protect, more negative coroner inquests, a further delegitimisation of policing meaning less intelligence, less co-operation and overall falling performance which (monitored by HMICFRS) will result in more police organisations in special measures. A cycle of demand failure and collapse will impact public outcomes and confidence but also working conditions, morale, attrition and recruitment.

More together

The Home Office in 1991 commissioned James Morgan to chair a national enquiry about how to make policing more effective by working in partnership. It has been recognised for some time that the police cannot, alone, stop crime by arresting their way out of it. If it could, given the number of arrests made over the years, we wouldn’t be facing the crime levels and prison crisis of today. Hence policing, alone, no matter how hard it tries, does not work. The Morgan Report (1991) advocated greater holism (working together across partnerships) and local democracy (using the insights of public end users more to inform priorities) to both enhance productivity but also public confidence.

The insights were adopted in the main within the Crime and Disorder Act (1998), particularly in the creation of Section 17 of the Act. Chambers (2009) reviewed the empirical evidence of prevention to conclude that less crime equated to reduced costs, which could be best achieved through upstream (proactive) preventative partnerships. Such conclusions remain true across all crime, but specifically to particular types such as violence (knife crime, VAWG etc), including anti-social behaviour.

We cannot afford a reactive model

Policing costs and productivity benefit analysis are affected by demand, much of which is not traditional crime enforcement. Positioning an organisational relationship based upon demand places it in a precarious reactive function, which it neither wants, nor can cope with. Of course, efficiencies can be sought through automation, but as the reactive model itself is unsustainable this simply amounts to doing the wrong thing, better.

Tier 1 (proactive prevention) is the better alternative by coalescing partnership collaboration focused upon common mission-based goals which prevent trouble rather than having to then continually respond to it. Tier 1 approaches can involve designing out crime. But at the psycho-socio-political level (such as easing poverty vulnerabilities), not just target hardening (put a lock on it).

Target hardening presumes rational choice theory opportunism as the key motive to offending behaviour (Cohen & Felson, 1979; Clarke, 2018), but despite this having become a traditionally favoured choice for policy makers, has been shown not to work over time. For example, shoplifting nowadays rejects all of the previously presumed target hardening tactics as simply irrelevant.

Tier 2 (reactive prevention) focuses upon an existing identified situation and seeks to problem solve out of it to prevent a re-occurrence, then moves to the next problem. Tier 2 prevention, whilst better than Tier 1-3 reactive, is still reactive in nature; at its worst problem solving can deteriorate into Ground Hog Day Whac-a Mole.

Prevention Hubs

Tier 1 and 2 thinking was evident at the first Crime Prevention unit formed in the UK, initially at Staffordshire Police HQ by then Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson. Now, new research from the University of Staffordshire, is refreshing thinking to drive a 21st century future-fit iteration that prevention is better than cure; which is now needed more than ever given the national budgetary context.

Prevention Hubs need a capacity and capability for Tier 1 and 2 prevention, with an understanding that Plan A needs to be Tier 1, whilst still possessing the dynamic agility to deliver Tier 2 where practical circumstances dictate. Tier 1 is a form of longer term strategy, Tier 2 is a form of ‘here and now’ coping mechanism tactic, but both are complementary and mutually supportive, as relying on just one, without the other, will result in unsustainable failure demand overload.

Aligning Tier 1 and 2 prevention

Tier 2 development has been substantial, thanks in the main to Professor Lawrence Sherman (2020), but there is a need to upscale Tier 1 investment to balance this vital relationship. Methods used to establish the evidence base to Tier 2 (including counter predictivity factors) now need to be more equally applied to Tier 1, mapped against cost benefit return efficacy, for a contemporary contextualised toolkit for partners and communities. This would create a stronger collaborative partnership that will be sustainable: cutting crime, cutting costs and growing public confidence in being safe through the valuable contribution of policing and partners.

New research (Coxhead, Pancholi and Uduwerage-Perera) is being published by Springer (New York) in 2025 and a working group, led by Dr Roy Bailey, is currently promoting policy adoption by the new Labour Government, aided by Professor Stan Gilmour’s Evidence Based Policing 3.0 Toolkit at Oxon Advisory Recent Publications (oxonadvisory.com).

Originally published on 16 October 2024 in EMPAC News

From Words to Action: A Call to End Violence

By Graham Goulden, Independent Trainer and Oxon Advisory Associate

It was a damp, rainy day in October 2013. I was traveling from Edinburgh to Perth to speak at a violence prevention event, four years into my 18-month secondment with the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit (!). I was passionate about their message:

“Violence is preventable, not inevitable”

Leaving the train station, my eyes were drawn to the front page of a newspaper. A young man's face stared back at me. I recognised him. He was 22, a new father, someone I'd worked with briefly. The headline confirmed my fear: he had been murdered in a knife attack.

In the UK, many believe violence won't touch them. That's a dangerous mindset. Violence can impact anyone, directly or indirectly.

This was brought home recently when I read about a 15-year-old boy stabbed on a London street. A passerby rushed to his aid, hearing the boy plead, "I'm 15, don't let me die." The trauma of this event will scar the bystanders, the victim’s family, the Good Samaritan, and the community. What shocked me further was the lack of media coverage. Have we become so desensitised to violence that the murder of a child barely registers?

At the Labour party conference, the Home Secretary pledged to halve knife offences within a decade. It's ambitious but achievable with proper resources. We need action, not just words or summits. We also need to reframe the conversation. If we don't talk about the issue correctly, how can we address it?

I've dedicated 15 years to violence prevention. Even after retiring from the police service, seven years ago, my passion for tackling this issue burns strong. As French General Ferdinand Foch said, "The most powerful weapon in the world is the human soul on fire." We all have a role to play. Less violence benefits everyone. We'll feel safer and pay less in taxes. Addressing violence is costly, and those costs are borne by taxpayers.

Poverty and hopelessness are major contributors to violence, but there are other ways we can all get involved in long-term prevention and see quicker results by doing more of what works, and less of what doesn't.

Here are my top ten insights to reduce violence:

We don't have all the answers, and we can't arrest our way out of this problem. My 30-year police career taught me the power of healthy relationships and community in preventing violence.

Building relationships underpins all these points. Better relationships lead to less violence, which leads to better schools and a healthier society. This is the goal: a safer society, free from violence.

Let's work together to make it a reality!

Graham Goulden is a retired Scottish police officer. The last years of his career were spent as a Chief Inspector with the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit. Now Graham is a leadership and violence prevention trainer. He is a passionate advocate for using the bystander approach to engage communities to help address levels of harm in society, in workplaces, in schools, and in sports teams. He works nationally and internationally and is a sought-after speaker and trainer about violence prevention. Graham has in recent years supported the development of successful prevention campaigns aimed at engaging men in the prevention of violence.

To learn more about Graham's work and how you can get involved in violence prevention efforts, please visit our Associates page or connect with him via his website or on social media.

Together, we can create a safer and more peaceful world for everyone.

Systems Leadership and Data Collaboration: Unlocking Productivity in Policing

Whole Systems

The Policing Productivity Review underscores the critical role of public trust and a "whole-system" approach in enhancing productivity within policing. This approach emphasises collaboration with various sectors, including education, social services, and technology, recognising that policing alone cannot address complex challenges. Data sharing is fundamental to this collaborative model, facilitating research, knowledge transfer, and informed decision-making. While the specific term "systems leadership" isn't explicitly used, the review implicitly calls for it by recognising the need for leaders who can think beyond organisational boundaries, foster collaboration, and drive change across the entire system.

Key Recommendations

- Cultivate a culture focused on effectiveness: Prioritise approaches and strategies that have proven track records of success.

- Data-driven decision-making: Utilise data to inform decisions, ensuring resources are used effectively and efficiently.

- Embrace a "whole-system" approach: Collaborate with partners across sectors to identify and address the root causes of crime.

- Leverage technology: Adopt technological solutions to improve productivity and streamline processes.

Importance of Data Collaboration

Data plays a crucial role in supporting a whole-system approach. The review highlights the current limitations of data sharing between agencies, stating that "forces view data as broadly for their own local use." To overcome this, the review suggests harmonising and sharing data across agencies, enabling:

- Enhanced research capabilities

- Improved knowledge transfer

- More informed decision-making

The Role of Systems Leadership

While not explicitly mentioned, the concept of "systems leadership" is woven throughout the review's emphasis on a whole-system approach. This leadership style is characterised by:

- Recognising the limitations of policing in isolation: Understanding that collaboration with other sectors is essential to address complex challenges.

- Promoting cross-sector collaboration: Actively working with partners in education, social services, technology, and other areas to achieve common goals.

- Prioritising data sharing: Facilitating the harmonisation and sharing of data between agencies to improve knowledge transfer and decision-making.

- Establishing a national community safety board: Creating a platform for senior representation from various sectors to address strategic issues and drive change.

In summary

By embracing the recommendations of the Policing Productivity Review and fostering systems leadership, the police can aim to improve productivity and reduce harm, regaining public trust, and delivering better outcomes for their communities.

Data collaboration is essential for informed decision-making and effective collaboration across sectors.

Reframing the Debate: From OCGs to OCBs

Organised criminals are savvy operators, driven by profit and adept at adapting their modus operandi and the commodities they trade to ensure a steady cash flow and expansion of their activities. As organised crime becomes increasingly transnational, Organised Criminal Groups (OCGs) have started mirroring the structure and methods of big businesses.

Dr Chris Allen of Oxon Advisory argues that it’s time to rethink how we talk about these entities.

Albert Einstein once said, “The more I learn, the less I know.” While he wasn’t referring to organised crime, the sentiment applies to understanding these groups. Despite extensive intelligence databases, investigations into organised crime often yield more questions than answers.

Winston Churchill’s description of Russia during WWII as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma” is equally applicable to organised crime. Due to the secretive nature of these activities, many key aspects of how organised crime operates remain unknown, despite numerous researchers delving into the subject.

However, it’s widely acknowledged in both policing and academia that organised crime functions like a business. This emerging concept suggests that OCGs operate similarly to legitimate businesses, with their commodity being illegal. Wainwright notes that drug cartels have learned “brand franchising from McDonald’s, supply chain management from Walmart, and diversification from Coca-Cola.” When OCGs start thinking like big businesses, the only way to understand them is through economics.

Over the past 40 years, the internationalisation of organised crime has led to increased sophistication. The structural and organisational similarities to legitimate businesses suggest that business analysis techniques can be applied to these illicit groups.

During my PhD research at Liverpool John Moores University, I explored this area extensively. My research focused on the ‘pursue’ element of the government’s organised crime strategy, applying legitimate business modelling techniques to illicit enterprises. By utilising established economic analysis techniques, we aim to enhance policing intelligence and improve strategies to pursue and disrupt organised criminal networks.

This approach aids in developing tactical and investigative strategies against these groups. Currently, such strategies are often informal and fail to account for the complexities of modern organised crime and its alignment with legitimate business practices.

My research demonstrates the strength of the connection between business analysis and organised crime. Through a detailed multimethodology approach, key questions from business analysis can be adapted to enhance the approach to organised crime, particularly in developing formal investigative strategies to dismantle these groups.

Substantial engagement with law enforcement and academic experts in business analysis and policing has cemented the validity of this approach. The overriding conclusion is that business analysis techniques can be transposed from legitimate business contexts to criminal investigations. These techniques can enhance investigations and provide insight into strategy development.

This work has culminated in the creation of the Utilising Business Analysis Towards Targeted Law Enforcement (U BATTLE) toolkit. This toolkit enhances the ability of police officers and analysts to think differently and generate alternative solutions to the problems posed by OCGs.

Literature supports the effectiveness of business analysis techniques in assessing the strengths and weaknesses of businesses. Given that organised crime operates like a business, it stands to reason that these techniques can also be applied to combat organised crime groups.

It’s time to rethink how we discuss these entities. Think Organised Criminal Businesses (OCBs), not OCGs!

Dr Chris Allen will explore this topic further with Prof. John Coxhead and Dr Michael Harrison at the upcoming NPCC Serious Organised Crime Conference on Friday, 12 July 2024.

Link to Chris’ CV Here

What to do about ‘knife crime’?

By Prof. Niven Rennie -

Oxon Advisory Associate

Last night 'knife crime' was once again one of the lead stories on Sky News. It is a story that has been doing the rounds across the media for years. Each time there is a horrific incident the experts appear - the calls for tougher sentencing, increased stop and search and despair at the state of the nation’s youth! I have previously been asked to contribute to a Radio 5 Live discussion on the introduction of tighter protective measures at our schools including ‘Ferrogard Poles’. It’s ‘Groundhog Day’ on steroids and nothing ever changes.

Public Health Issue

In 2002 the World Health Organisation Report on Violence and Health declared violence to be a ‘public health issue’. Such an issue can only be addressed by a whole system preventative approach. We have known this for over 20 years but, despite this, we still react to the symptom and not the cause. It would be like treating the cough element of COVID and hoping the disease would not spread whilst ignoring the need for the vaccine that would bring about the return to normal life. In simple terms, the responsibility for addressing violence lies outside the justice system – once we are discussing arrest and sentencing, we have let the problem multiply to a stage where it has become rampant and out of control.

The Role of the Police

There is doubtlessly a role for the police and search is a tool that can be very effective where violence presents. The aim of a progressive society, however, should surely be to prevent the violence from taking place in the first place. Again, policing has a part to play here but not the primary role.

Social Factors

In Scotland, 1% of the population experience 65% of violent crime. They are the same individuals who have the worst health and educational outcomes, are more likely to be addicted to gambling, drugs or alcohol and have their life trajectory dictated to them from birth. They are to be found in our poorer communities. They grow up with a lack of hope, aspiration, and ambition. When you have no hope the threat of an increased sentence is no deterrent. Research has shown that a significant number of our prison population are care experienced…. failed by society time and time again.

The Cost of Prison

The justice system is not free. Prosecution costs a significant amount and each person we place in prison costs society £50K a year or thereby. Could we spend that money in a more preventative manner?

The Violence Industry

We need to invest properly in our youth. Provide mentors, activities, and support. There are numerous successful ventures that have reduced violence, but they are sporadic and ill funded. We make funding available but require applicants to jump through hoops to access same. Most applications are rejected, and the funds are overseen by teams of decision makers who receive significant salaries – that is the youth violence industry.

A Call for Action

Here's the answer to tackling knife crime: Change the approach. Support young people, acknowledge their potential, invest in their futures, and foster hope instead of punishment. This means adopting a public health model – proactively preventing the problem, leading to better outcomes, fewer victims, and a wiser use of societal resources.

The question is: Do our leaders have the courage and imagination to make that change?

The Oxon Advisory Mindset:

Beyond Problem-Solving, a Vision for Preventive Solutions.

Oxon Advisory is a pretty unique thing. It’s a mindset about the continual improvement of policing, community safety, and wellbeing. The mindset is characterised by an incessant curiosity of how things work, of hopeful ambition to seek something better for the future, and a spirit of enterprise to be open minded to listen to new ideas to promote our goal - Safe and Thriving Communities.

A public service ethic

What unites those working in Oxon Advisory, I believe, is the public service ethic of policing, to protect people from harm and find ways ultimately to reduce, and prevent, crime. That ethic is about understanding that crime is in many ways a symptom of circumstance, linked to underlying factors such as poverty and trauma. But the ethic also understands that serious organised crime businesses purposefully exploit the vulnerable and that such criminal enterprises need dismantling with intelligence-led enforcement and disruption vigour.

Policing is such an important public service that it can’t be left just to the police to decide how to do things, it needs active community involvement and scrutiny accountability. It also needs diverse perspectives, that are informed by our rapidly changing world, to ensure it is upstream and not simply reactive.

Collaborative thinking

For some time, there has been a reliance upon the University sector to lead expertise about policing, but there is now a change, increasingly leading to a mature state of ‘praxis’ where theory and practice intertwine like a dynamic Yin and Yang helix. This new maturity values the richness of co-problematisation and co-production of ideas and insights, unifying empirical data and professional experience as equal partners to dynamically inform the professional skills of policing and community safety, and wellbeing partners.

Unfortunately, there are too few within the University sector alone who understand enough about the implementation of theory into practice. Similarly, there are too many within policing itself who are not prepared to listen to new ideas. Somewhere there is a middle ground, and that is where Oxon Advisory operates, blending research with policy design, collaboration, and wide experience of implementation.

Exploring the future

The direction of travel now should be to accelerate towards the future by working on a solution-oriented approach, to go beyond the limitations of reactive problem-solving and focus on what we do want from the police and their partnerships, and not be perpetually distracted about how to ameliorate what we don’t.

That is about setting a compass. Our ‘true North’ will be what good will look like in the future. Using a compass will be about having direction but also creatively using our skills of enterprise to get us where we need to be, just as those before us have done so in every scientific, industrial, and social evolution.

We are, effectively, explorers, motivated by ‘what if?’ we could be better, be more, than we currently are.

Work with us and together help make the future of policing, community safety and wellbeing as good as it can be, building Safe and Thriving Communities.

By Prof. John Coxhead SFHEA FRSA –

Oxon Advisory Associate

From Data Doubters to Data Wizards

Boosting Data Literacy: Strategies for Data-Driven Organisations

Improving data literacy across teams and organisations is a key challenge for leaders focused on data-driven decision-making. However, the payoff is significant! When your team understands data, they unlock benefits like:

- Smarter Decisions: Replace guesswork and assumptions with evidence-based choices, leading to better outcomes.

- Problem-Solving Prowess: Data literacy empowers employees to identify the root cause of issues rather than just addressing symptoms.

- Efficiency Gains: Uncover ways to streamline tasks, optimise processes, and eliminate waste by analysing the right data.

- Competitive Advantage: A data-savvy team spots trends, needs, and opportunities others miss.

Strategies to make this happen:

Foundational Steps

- Assess Current Skill Levels: Before you design solutions, get a sense of where people are starting. Conduct surveys, interviews, or simple skills assessments to understand the baseline data literacy across the organisation.

- Define the Mission: Why is this important for your organisation? What specific goals, results, or benefits do you expect from improved data literacy? Being clear about this helps tailor your strategies and communicate the value to your team.

- Leadership as Champions: Leaders need to demonstrate commitment. They must use data in their own decision-making, talk about it openly, and visibly celebrate examples of successful data-driven work.

Methods for Building Data Literacy

- Prioritise Accessibility: Make sure employees can find the data they need, it's well organised, and there's a data dictionary or resource explaining key terms and metrics. Confusion about where to find things is a huge barrier.

- Tailored Training: Don't throw everyone into the same generic analyst course. Design training paths specific to roles and current skill levels:

- Data Fundamentals: Core concepts (data types, statistics basics, visualisation principles) for everyone.

- Role-Specific Skill Building: Deeper dives for those who directly analyse data (e.g., business analysts, marketers). This might include tools like Excel, SQL, or BI software.

- Data Storytelling: For those presenting findings to others, focus on translating insights into compelling narratives.

- Mentorship and Communities: Pair data-savvy individuals with those needing support. Encourage a 'data community' where people can share tips, success stories, and troubleshoot together.

- Celebrate Data-Driven Success: When projects are successful because of good data use, highlight them! This reinforces to everyone the benefits of investing in data literacy.

Additional Considerations

- The Long Game: Data literacy is a cultural shift, not a one-time workshop. Build it into your ongoing learning and development strategy.

- Small Wins: Start with targeted projects where the value of data becomes apparent quickly to build a sense of momentum.

- Emphasise Curiosity: Data skills shouldn't be about blind compliance. Foster an environment of asking good questions, challenging assumptions, and using data to uncover new opportunities.

Here are the 7 best uses of linked public data:

To reduce health disparities and improve community safety and well-being

1. Enhanced Collaboration and Data-Driven Partnerships

- The Problem: Health, community safety, and wellbeing often involve different agencies working together with disconnected data.

- How Linked Data Helps: A shared data infrastructure enables interagency collaboration. This leads to coordinated actions, efficient use of resources, and holistic approaches to complex problems.

- Example: Connecting health data with housing records and social service data can facilitate streamlined processes to help someone experiencing homelessness access necessary medical care, housing assistance, and job support.

2. Identifying and Addressing Social Determinants of

Health (SDOH)

- The Problem: Factors like income level, access to education, quality housing, and to healthy food vastly influence health outcomes. These social determinants can lead to significant health disparities.

- How Linked Data Helps: By connecting data on housing, employment, and education with public sector data, public agencies can identify the communities and populations most affected by SDOH. This information targets resources, early help, and interventions for maximum impact.

- Example: Mapping areas with both high rates of chronic disease and poor food access can trigger local initiatives such as supporting community gardens.

3. Predictive Modelling of Risk and Protective Factors

- The Problem: Understanding areas at risk for health problems or community safety issues, and their access to protective resources is crucial for prevention.

- How Linked Data Helps: Analysing multiple data sets on crime rates, demographics, environmental factors, and social conditions reveals patterns. This helps build predictive models for preventive interventions.

- Example: Correlating data on poverty, lack of green spaces, and historical crime patterns could guide city planners to introduce safety measures or transform neglected areas into vibrant community spaces.

4. Early Identification of Vulnerable Populations

- The Problem: Often, high-risk groups go unnoticed until a health crisis or safety issue occurs.

- How Linked Data Helps: Cross-referencing health data, social service records, police information, income levels, and other indicators identifies individuals or communities needing additional support.

- Example: Analysing data on food insecurity, school attendance records, and health indicators flags children experiencing challenges that might jeopardise their wellbeing and educational future.

5. Targeted Resource Allocation

- The Problem: Limited resources must be used effectively to address the most pressing areas of need and ensure services reach the people most at risk.

- How Linked Data Helps: Comprehensive data analysis guides decision-makers on where to invest health funding, deploy preventive programs, and focus community safety initiatives.

- Example: A town analysing data finds a correlation between poor lighting, high crime rates, and low usage of public parks after dark. These insights inform decisions to invest in improved lighting.

6. Performance Evaluation of Programs and Policies

- The Problem: Accurately measuring the effectiveness of health and wellbeing interventions is vital for improvement.

- How Linked Data Helps: Comparing datasets before and after program implementation reveals the real-world impact. This guides refinements and more effective resource allocation.

- Example: Tracking crime statistics, demographics, and data on a newly implemented neighbourhood policing program can demonstrate whether the program is decreasing crime, improving public perception of safety, and building trust. Randomised Control Trials of interventions can add a significant layer of robust testing.

7. Promoting Transparency and Accountability

- The Problem: Communities need visibility into the decision-making processes affecting their well-being.

- How Linked Data Helps: Publicly accessible data visualisations and dashboards allow citizens to understand trends and see how their tax money is being used. This promotes engagement and fosters trust.

- Example: Interactive maps showing health disparities, crime trends, and program outcomes empower communities with information for holding leaders accountable.

Important Considerations:

- Data Privacy: Robust safeguards must be in place to protect personal information while facilitating responsible data use.

- Data Quality: Accurate, up-to-date, and standardised linked data are critical for meaningful analyses.

- Data Literacy: Communities and leaders alike need training and support to fully leverage linked data potential.

The Five Leadership Traits for Effective Data Collaboration.

With a focus on community safety and wellbeing:

1. Communication and Transparency

- Plain language communication: Leaders in this space must translate complex data concepts into digestible information for residents, community groups, and politicians. Effective leadership emphasises the 'why' – how data informs better community outcomes.

- Public-facing transparency: Proactive publishing of anonymised data sets and findings builds public trust. Clear explanations of how data is used (and not used) are essential, including ethical considerations.

Why it matters in the public sector: Fostering trust with the public is paramount. Openness about how data drives decisions will help to secure buy-in and minimise the potential for misuse.

2. Vision and Strategy

- Community-centric vision: Data initiatives must go beyond crime reduction. Leaders should envision how data can improve social determinants of health, early intervention programs, and address systemic inequities.

- Cross-sector collaboration: Leaders develop roadmaps that involve agencies beyond policing (e.g., housing, health, education). This requires a shared definition of "community safety" and coordinated goals.

Why it matters in the public sector: Holistic approaches to community safety and wellbeing are more effective. Breaking down silos between agencies allows for proactive problem-solving and addressing root causes.

3. Inclusivity and Empowerment

- Resident and advocate involvement: Leaders actively seek input from diverse community voices. They create mechanisms for this collaboration that are accessible and meaningful (not tokenising).

- Upskilling frontline workers: Leaders provide training and empowerment to staff involved in data collection and interpretation. This ensures data isn't just a top-down tool but informs day-to-day interactions and service delivery.

Why it matters: Addressing power imbalances builds trust. Those closest to residents have valuable knowledge that data must enrich, not supplant. Upskilling frontline staff ensures data creates actionable insights.

4. Technical Understanding and Adaptability

- Emphasis on data quality and governance: Leaders prioritise data accuracy and robust governance practices to protect individual privacy. They understand ethical implications of data use within a public mandate.

- Adapting to evolving public concerns: Leaders keep abreast of changing community needs, social issues, and public sentiment regarding data-use. Agility and responsiveness are essential as technologies develop.

Why it matters: Ethical and accurate data practices are non-negotiable. Leaders must be sensitive to public fears of surveillance while maximising benefits. Remaining flexible about how data is used in different contexts maintains legitimacy.

5. Advocacy and Stakeholder Management

- Championing data-driven decision-making: Leaders actively advocate for the use of data within the organisation and beyond. They educate decision-makers on its potential benefits and challenge resistance to change.

- Building relationships and managing diverse stakeholders: In the public sector, this includes navigating relationships with politicians, community groups, businesses, partner agencies, and the media - who all have varying priorities.

Why it matters: Leaders need to secure buy-in, funding resources, and address public concerns. Skilfully managing diverse stakeholders and partnerships is often the difference between a stalled project and a successful initiative that improves lives.

Building Capacity for Trauma-Informed Communities:

How Early Help makes a difference.

This blog post explores the importance of early intervention and building capacity for trauma-informed communities, drawing insights from a report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) on the impacts of Sure Start, a program that provided holistic support to families with children under five in England.

The IFS report highlights the significant benefits of early help programs like Sure Start. The program aimed to improve the development and life chances of children, and the findings demonstrated that it achieved its goals. Children who participated in Sure Start showed improved academic achievement and reduced need for special educational services. These benefits were particularly pronounced for children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The report's findings underscore the critical role of early help in fostering positive outcomes for children. Early intervention programs can equip children with the tools they need to thrive in school and later life. They can also help address potential developmental delays and prevent the need for more intensive interventions later on.

Here are the report’s key findings:

- Improved GCSE performance: Children who participated in Sure Start showed better performance in GCSEs, a set of exams typically taken by 16-year-olds in England. This suggests that Sure Start can help children develop the skills and knowledge they need to succeed in school.

- Benefits for disadvantaged children: The positive effects of Sure Start were particularly pronounced for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. This finding highlights the program's potential to help close the achievement gap between children from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

- Early identification of special needs: The report also found that Sure Start increased the likelihood of a child being identified with special educational needs (SEN) at a young age. This may seem like a negative outcome, but early identification can allow children to receive the support they need to thrive and prevent contact with justice services.

- Reduced need for SEN support later: Interestingly, the study also found that children who participated in Sure Start were less likely to need SEN support later in school. This suggests that early help can help address potential developmental delays and prevent the need for more intensive, sometimes punitive, interventions later on.

Overall, the findings of the IFS report suggest that Sure Start was a cost-effective program that improved educational outcomes for children, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds. The program appeared to achieve this by equipping children with the skills they needed to succeed in school and by facilitating early identification, help, and intervention for those with special educational needs.

The Human and Community Costs of Late Intervention

When children's needs are not addressed early on, it can lead to a cascade of negative consequences. Children who experience trauma or developmental delays may struggle in school, face social and emotional challenges, and be more likely to engage in risky behaviours and encounter justice services. These issues can have a ripple effect, impacting their families, communities, and society.

Late intervention can have several negative consequences for both individuals and communities. These can include:

- Higher costs: When problems are not addressed early on, they can become more severe and expensive to treat later. For example, a child who does not receive early help for speech delays may require more intensive speech therapy later in life.

- Increased need for special services: Children who experience developmental delays or other problems are more likely to need special education services or other forms of support. This can put a strain on school budgets and resources.

- Social and emotional problems: Children who do not receive early intervention may struggle in school and have difficulty forming relationships with their peers. They may also be more likely to experience mental health problems, such as anxiety or depression.

- Criminal justice involvement: Children who experience trauma or other forms of adversity are more likely to become involved in the criminal justice system earlier in like and remain in contact as adults.

These are just some of the human and community costs of late intervention. Early help programs can help to prevent these problems and promote positive outcomes for children and families.

Building Capacity for Trauma-Informed Communities

Considering the evidence on the benefits of early help, we must advocate for building capacity for trauma-informed communities. Trauma-informed communities are those that recognise and understand the impact of trauma on individuals and families. They create safe and supportive environments where people can heal and thrive.

Here are some key steps towards building trauma-informed communities:

- Education and Awareness: Raising awareness about childhood trauma and its effects is crucial. Communities can organise workshops, training sessions, and educational campaigns to equip people with the knowledge and skills to support those who have experienced trauma.

- Support for Families: Families play a vital role in a child's development and healing process. Communities can provide support services for families, such as parenting programs, mental health resources, and access to affordable childcare.

- Collaboration: Building trauma-informed communities requires collaboration across different sectors. Schools, healthcare providers, social services, police, and community organisations can work together to create a coordinated system of care that meets the needs of children and families who have experienced trauma.

By investing in early help and building capacity for resilient and trauma-informed communities, we can create a brighter future for our children and society.

Contact Oxon Advisory to discuss your needs, our Associates are global leaders in Trauma Informed Policy and Practice.

How to become a Time Lord in Public Safety Decision-Making

Reflections from OXA CEO, Prof. Gilmour

During my 30-year police career I became a qualified and experienced Senior Investigating Officer for Major Crime, Homicide, Kidnap and Extortion, Covert Operations and Counterterrorism as well as a Strategic Firearms (Gold) Commander. I ran two modules on the UK’s College of Policing national PIP 4 Course (Professionalising Investigation Programme Level 4), covering threats to life and critical incident (counterterrorism) command and response - and one on the Joint Emergency Services Interoperability Principles (JESIP) course at the national Fire Service College. The PIP 4 course is designed for senior police professionals responsible for the strategic management of complex investigations. This intensive course focuses on developing essential leadership and command skills for those overseeing high-profile or challenging cases. It covers key themes such as strategic partnerships, resource management, information and intelligence handling, and maintaining public confidence. The PIP 4 course aims to provide Senior Investigating Officers with the knowledge and tools needed to make sound, strategic decisions while upholding the highest standards of investigative practice.

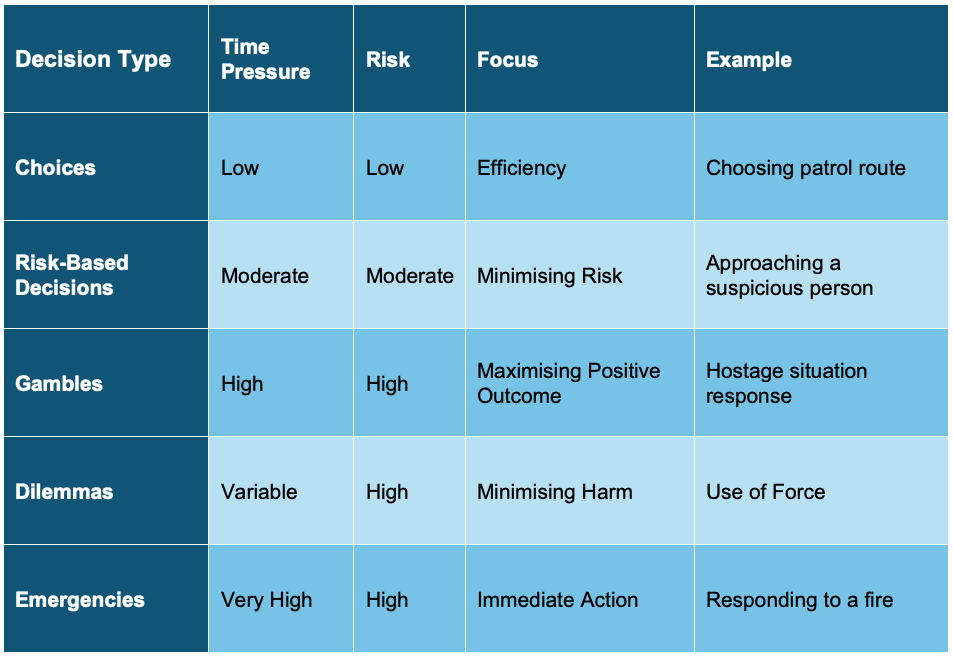

Through my work, and my research, I concluded that one of the key determinants of success in managing critical incidents is - Time. The more time you have the more options you may have, I taught senior leaders how to create the time they needed. Here's a breakdown of decision-making in public safety, highlighting the key differences with respect to time:

Choices: These are everyday decisions with minimal risk and often ample time. Public safety officers might choose between patrolling a specific route or responding to a minor noise complaint. Here, time allows for gathering information and weighing options before action.

Risk-Based Decisions: These involve calculated risks based on available information. Time may be limited, but not critically so. An officer responding to a suspicious person call might consider the potential threat, witness reports, and backup availability before approaching. Here, the decision aims to minimise risk while achieving the objective.

Gambles: These are decisions made with limited information and potentially high stakes. Time pressure is significant. In a hostage situation, an officer might need to choose between initiating negotiations or a tactical response with incomplete intel. Here, the focus is on maximising the chance of a positive outcome despite uncertainty. Gambles are sometime unnecessary choices, it’s important to understand if you are gambling.

Dilemmas: These involve difficult choices with potentially negative consequences regardless of the decision. Time might be available, but the situation presents a moral or ethical conflict. An officer might face a dilemma involving using force against a suspect resisting arrest but potentially harming a bystander. Here, the focus is on finding the least harmful option.

Emergencies: Here, split-second decisions are required with little to no time for deliberation. Public safety officers encountering a fire, or a violent crime may need to react instantaneously based on training and instinct. The priority is immediate action to mitigate harm.

Here's a table summarising the key points:

Better outcomes for children and young people with an Acquired Brain Injury (ABI)

Click on the link to read Prof. Gilmour's interview with T2A, about how early intervention could prevent children and young people with an Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) from coming into contact with the criminal justice system.

https://t2a.org.uk/2024/03/26/cyp-acquired-brain-injury/

26 March 2024

The 5 Data Sins, and their solutions:

1. The Hoarding Impulse

- Solution: Build a culture of collaborative data sharing.

- Create governance structures that outline clear data ownership, access protocols, and security standards.

- Promote the use of shared data platforms and APIs for seamless data collaboration.

2. Quality Blindness

- Solution: Prioritise data quality throughout the lifecycle.

- Establish rigorous data collection standards and validation processes.

- Implement regular data cleaning and auditing to maintain accuracy.

3. Privacy Paranoia

- Solution: Earn trust through transparency and ethical use.

- Develop clear privacy policies that are easily accessible to the public.

- Utilise privacy-preserving techniques like anonymisation and differential privacy.

- Obtain informed consent from individuals when appropriate.

4. Ignoring Context

- Solution: Combine data with community knowledge.

- Engage community members in data collection and interpretation.

- Integrate qualitative data (e.g., resident surveys, interviews) for a richer understanding of needs and challenges.

5. Analysis Paralysis

- Solution: Focus on actionable insights.

- Frame data analysis around specific questions relevant to community wellbeing.

- Communicate results through clear visualisations and plain language.

- Develop action plans that translate data into concrete interventions.

Important Note: These solutions won't work without strong leadership that champions data-driven decision-making and community collaboration.

Summary of James Smart Memorial Lecture 2023 by Prof. Gilmour

Collaborative Prevention: The Power of Working Together for the Common Good

This lecture was delivered by Professor Stan Gilmour at the Scottish International Policing Conference in November 2023. The lecture focused on the importance of collaboration between police, other public agencies, and community partners in order to build safer communities.

Summary of the lecture

The lecture begins by outlining the main challenges facing policing today. It then reflects on the policing environment faced by Chief Constable James Smart in the mid-19th century.

Professor Gilmour argues that there are continuities between the challenges faced by police today and those faced by Smart in the 19th century.

He also highlights the importance of public health approaches to community safety and well-being.

The lecture emphasises the importance of data collaboration as a foundation for building partnerships between police, other public agencies and community partners.

Professor Gilmour argues that data collaboration is essential if we are to win hearts and minds and achieve the full potential of collaboration.

He also highlights the importance of addressing missed opportunities and gaps in data collection. For example, he argues that there is a paucity of data on how to intervene effectively with girls, women, and those with neuro-disabilities.

The lecture concludes with a note of hope for the future of data partnerships. Professor Gilmour believes that by working together, we can build the scaffolding for collaborative prevention.

Key takeaways from the lecture

- Collaboration between police, other public agencies, and community partners is essential for building safer communities.

- Data collaboration is a key foundation for building effective partnerships.

- We need to address missed opportunities and gaps in data collection in order to improve our interventions.

- There is hope for the future of data partnerships. By working together, we can build a safer future for all.

In addition to the summary above, the lecture also covered the following topics:

- The importance of evidence-based policing

- The role of the police in promoting public health

- The need for a holistic approach to community safety